Table of Contents

Cross-chain asset swaps face a trust problem. Exchanging Token-A for Token-B across blockchains through a centralized exchange requires both parties to trust the exchange with their funds. If the exchange colludes with one party or fails during the swap, the other party loses their assets. Within a single blockchain, decentralized exchanges like Uniswap solve this using smart contracts as trustless intermediaries. Atomic swaps extend this trustless exchange model across different blockchains without intermediaries.

What Are Atomic Swaps?

Atomic swaps enable direct peer-to-peer exchange of assets across different blockchains without intermediaries. The term "atomic" means the swap executes completely or not at all, with no partial states. If Alice wants to trade Bitcoin for Bob's Ethereum, an atomic swap ensures either both parties receive their assets or both retain their original holdings. This eliminates counterparty risk.

The mechanism relies on cryptographic primitives that enforce this all-or-nothing property. Both parties lock their assets using conditions that can only be satisfied if the complete exchange succeeds. If either party fails to complete their side within a set timeframe, both locks expire and funds return to their original owners. Hash Time-Locked Contracts implement these conditional locks.

Hash Time-Locked Contracts (HTLCs)

HTLCs are conditional payments that combine two cryptographic primitives: hashlocks and timelocks. The hashlock ensures only the intended recipient can claim funds by requiring knowledge of a secret. The timelock guarantees the sender recovers their funds if the recipient fails to claim within a deadline.

HTLC Construction and Protocol

A hashlock gates fund release on knowledge of a preimage. The sender locks funds with a hash H. The recipient can only claim by revealing secret S where hash(S) = H. A timelock gates fund release on time. After block height T or timestamp T, the original sender can reclaim locked funds regardless of the hashlock. This prevents funds from being permanently locked if the recipient disappears.

HTLCs support three operations: fund (initiator locks assets specifying hash, recipient, and timeout), redeem (recipient claims by providing preimage before timeout), and refund (initiator reclaims after timeout expires).

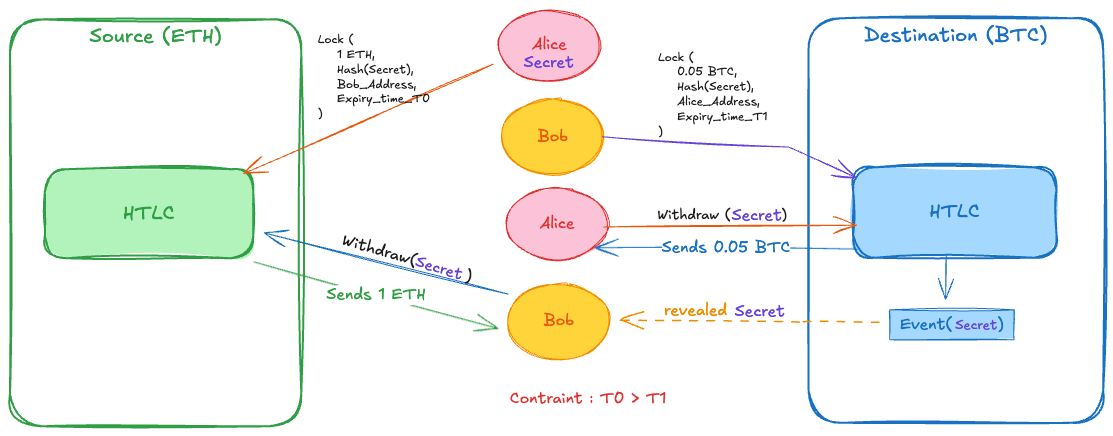

Consider Alice holding ETH and Bob holding BTC agreeing to swap at a predetermined rate. Alice generates a random secret S and computes H = SHA256(S). She creates an HTLC on Ethereum locking 1 ETH with hash H, Bob as recipient, and timelock T1 (48 hours). Bob monitors Ethereum, sees Alice's HTLC, and creates a corresponding HTLC on Bitcoin locking 0.05 BTC with the same hash H, Alice as recipient, and a shorter timelock T2 (24 hours). Alice redeems Bob's BTC by submitting a transaction that reveals S. This transaction is public on Bitcoin's blockchain. Bob extracts S from Alice's redemption transaction and uses it to redeem Alice's ETH on Ethereum.

The constraint T1 > T2 is critical. Alice must claim Bitcoin before T2, revealing S. Bob then needs time to observe S and submit his Ethereum redemption before T1. If T1 <= T2, Alice could wait until just before T2, claim BTC (revealing S), leaving Bob no time to claim ETH before Alice refunds it. The delta T1 - T2 must account for block confirmation times, network latency, and fee market congestion.

If Bob never creates his HTLC, Alice refunds after T1. If Alice never claims, Bob refunds after T2, then Alice refunds after T1. Both retain original assets. The swap is atomic: either both redemptions succeed or neither does.

Bitcoin Script Implementation

Bitcoin Script is a stack-based, non-Turing-complete language used to define spending conditions for UTXOs. Each output contains a locking script (scriptPubKey) that specifies what conditions must be satisfied to spend it, and the spender provides an unlocking script (scriptSig) with the required data.

BIP-199 standardized HTLC transactions for Bitcoin to enable atomic swaps and Lightning Network payment channels. Before BIP-199, implementations varied across projects, making interoperability difficult. The specification defines a canonical script structure that wallets and protocols can rely on.

OP_IF

OP_SHA256 <hash_digest> OP_EQUALVERIFY

OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <recipient_pubkey_hash>

OP_ELSE

<timeout> OP_CHECKLOCKTIMEVERIFY OP_DROP

OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <sender_pubkey_hash>

OP_ENDIF

OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIGThe script creates two spending paths controlled by OP_IF/OP_ELSE. The first path (redemption) requires the recipient to provide the preimage that hashes to hash_digest plus a valid signature. OP_SHA256 hashes the provided preimage, OP_EQUALVERIFY checks it matches the digest, then standard P2PKH opcodes verify the recipient's signature. The second path (refund) activates after the timeout. OP_CHECKLOCKTIMEVERIFY ensures the current block height or timestamp exceeds timeout, then verifies the sender's signature. The OP_DROP removes the timeout value from the stack after verification.

To redeem, the recipient constructs: <signature> <pubkey> <preimage> OP_TRUE. The OP_TRUE selects the first branch. To refund after timeout, the sender constructs: <signature> <pubkey> OP_FALSE. The OP_FALSE selects the else branch. The Decred atomicswap repository provides a complete Go implementation for cross-chain swaps, bcoin's swap guide walks through the full protocol and Bitcoin-Ethereum Atomic Swaps in Practice explains more about the bip-199 bitcoin script execution.

Ethereum Smart Contract Implementation

Unlike Bitcoin's script-based approach where spending conditions are embedded in the transaction output, Ethereum HTLCs use persistent contract state to track multiple concurrent swaps. A single deployed contract can manage many independent HTLCs, each identified by a unique ID derived from hashing the contract parameters. The contract maintains a mapping of these IDs to their respective lock states, amounts, participants, and deadlines.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.30;

contract HTLC {

struct Lock {

address payable sender;

address payable recipient;

bytes32 hashlock;

uint256 timelock;

uint256 amount;

bool withdrawn;

bool refunded;

}

mapping(bytes32 => Lock) public locks;

event Locked(bytes32 indexed lockId, address sender, address recipient, uint256 amount, bytes32 hashlock, uint256 timelock);

event Withdrawn(bytes32 indexed lockId, bytes32 preimage);

event Refunded(bytes32 indexed lockId);

function lock(address payable _recipient, bytes32 _hashlock, uint256 _timelock) external payable returns (bytes32) {

require(msg.value > 0, "Must send ETH");

require(_timelock > block.timestamp, "Timelock must be future");

bytes32 lockId = keccak256(abi.encodePacked(msg.sender, _recipient, _hashlock, _timelock));

require(locks[lockId].amount == 0, "Lock exists");

locks[lockId] = Lock(payable(msg.sender), _recipient, _hashlock, _timelock, msg.value, false, false);

emit Locked(lockId, msg.sender, _recipient, msg.value, _hashlock, _timelock);

return lockId;

}

function withdraw(bytes32 _lockId, bytes32 _preimage) external {

Lock storage l = locks[_lockId];

require(l.amount > 0, "Lock not found");

require(!l.withdrawn && !l.refunded, "Already settled");

require(keccak256(abi.encodePacked(_preimage)) == l.hashlock, "Invalid preimage");

l.withdrawn = true;

l.recipient.transfer(l.amount);

emit Withdrawn(_lockId, _preimage);

}

function refund(bytes32 _lockId) external {

Lock storage l = locks[_lockId];

require(l.amount > 0, "Lock not found");

require(!l.withdrawn && !l.refunded, "Already settled");

require(block.timestamp >= l.timelock, "Timelock not expired");

l.refunded = true;

l.sender.transfer(l.amount);

emit Refunded(_lockId);

}

}The Lock struct stores all state for a single HTLC: the sender who can refund, the recipient who can withdraw, the hashlock (keccak256 hash of the secret), the timelock (Unix timestamp), the locked amount, and two boolean flags preventing double-spending. The lockId is computed as keccak256(sender, recipient, hashlock, timelock), ensuring uniqueness per parameter combination.

The lock() function creates a new HTLC. The sender calls it with ETH attached, specifying the recipient address, hashlock, and future timelock. The function validates that funds are sent and the timelock is in the future, computes the lockId, checks no existing lock uses that ID, stores the lock state, and emits an event. The recipient monitors for Locked events to detect when their counterparty has funded.

The withdraw() function lets the recipient claim funds by revealing the preimage. It loads the lock, verifies it exists and has not been settled, then checks keccak256(preimage) == hashlock. If valid, it marks the lock as withdrawn and transfers ETH to the recipient. The emitted Withdrawn event contains the preimage, which the counterparty on the other chain can extract to complete their side of the atomic swap. Note that withdraw() has no timelock check since the recipient should claim as soon as possible, the preimage reveal is what matters.

The refund() function allows the sender to reclaim funds after timelock expiry. It verifies the lock exists, has not been settled, and that block.timestamp >= timelock. The sender can call this with any account since the funds always return to the original l.sender address stored in the struct.

For ERC-20 tokens, the pattern extends with transferFrom() replacing native ETH transfers, requiring prior approval from the sender. ERC-2266 standardizes this further by adding premium payments to compensate participants for the option-like exposure during the swap window.

Security and Limitations of Atomic Swap

Atomic swaps remove the need for trusted third parties but come with their own set of problems. The following are the main security issues and practical limitations.

Timelock Attacks and Griefing

Griefing occurs when one party intentionally abandons a swap after the other party has locked funds. The attacker loses nothing since they wait for their timelock to expire and refund, but the victim's capital remains locked until their longer timelock expires. In a standard HTLC swap with T1 = 48 hours and T2 = 24 hours, Bob can lock Alice's ETH for 48 hours at zero cost by funding his Bitcoin HTLC and then disappearing.

The attack scales poorly for the griefer since they must lock equivalent value, but the asymmetry in timelock durations means the victim always suffers longer lockup. A malicious actor can systematically grief counterparties, locking their liquidity repeatedly. Proposed mitigations include requiring upfront premium payments that compensate the victim if the swap fails. However, this introduces its own problem, the premium itself gets locked for the swap duration. Grief-free atomic swap constructions address this by restructuring the protocol so neither party can grief without penalty.

The Option Problem

Standard HTLC swaps grant the secret-holder a free option to complete or abandon the swap. After both parties lock funds, Alice can wait until just before T2 expires to decide whether to proceed. If the exchange rate moves in her favor during this window, she claims Bob's BTC. If it moves against her, she lets both timelocks expire and recovers her ETH. Bob has no such choice since he cannot claim without the secret.

This asymmetry becomes significant in volatile markets. If Alice locks 1 ETH for 0.05 BTC and ETH appreciates 20% during the swap window, she abandons the swap. If ETH depreciates 20%, she completes it. Either outcome favors Alice at Bob's expense. The optionality problem formalizes this, the secret-holder extracts value from the counterparty proportional to asset volatility and timelock duration. Solutions include premium mechanisms where Alice pays Bob an upfront fee, shorter timelocks to reduce the speculation window, or protocols like ERC-2266 that formalize explicit premium payments.

The Sleeping Vulnerability

The sleeping vulnerability occurs when the secret-holder goes offline after the counterparty locks funds but before revealing the secret. Bob's funds remain locked until T2 expires. Unlike griefing (which is intentional), this can happen due to network issues, hardware failure, or user error. The protocol cannot distinguish between an unavailable participant and a malicious one, so it must wait for timeout.

This also affects the secret-holder. If Alice claims Bob's BTC but then goes offline, Bob must extract the secret from Bitcoin's mempool and submit his Ethereum claim before T1. If Bob is unavailable during this window, he loses his ETH despite Alice completing her side. Both parties must remain online and responsive throughout the swap window.

The Liquidity DoS

Each HTLC locks capital for the duration of the timelock window. For market makers or frequent traders, this capital inefficiency becomes prohibitive. A market maker offering BTC/ETH swaps must maintain reserves on both chains, and each pending swap reduces available liquidity.

An attacker can exploit this by initiating many swaps simultaneously with no intention of completing them. The attacker's cost is transaction fees for creating and refunding HTLCs, the victim's cost is frozen capital for 24-48 hours per swap. This disproportionately affects liquidity providers who advertise swap availability.

Secret Management

Users must generate cryptographically secure secrets and retain them until the swap completes. Losing the secret before claiming means losing the funds since you cannot prove knowledge of the preimage. Revealing the secret prematurely (before the counterparty locks) allows them to claim without locking their side.

No gas on the Destination Network

Users may lack native assets on the destination chain to pay for the claim transaction. If Alice swaps ETH for BTC and has never used Bitcoin, she needs BTC to pay the fee for claiming from Bob's HTLC. This bootstrapping problem requires pre-funding destination wallets or using relayers who submit transactions on behalf of users, introducing trust assumptions or additional fees.

Modern Atomic Swap Protocols

TRAIN Protocol

TRAIN is a trustless cross-chain swap protocol that improves on classic HTLCs by introducing PreHTLCs and professional liquidity providers called Solvers. The protocol addresses the main pain points of traditional atomic swaps: secret management, gas on the destination chain, and the requirement for both parties to stay online.

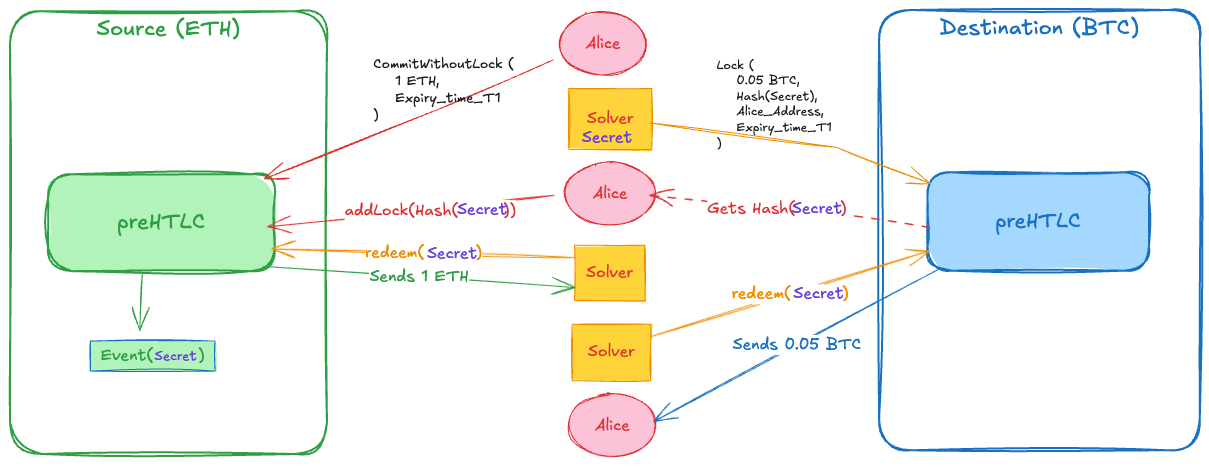

PreHTLCs

Classic HTLCs require users to commit with the full hashlock and timelock details upfront. This creates a timing problem where the user must lock funds before knowing if the counterparty will follow through. PreHTLCs solve this by splitting the process into two phases. First, the user creates a commitment without the hashlock. The Solver sees this commitment, generates the secret, and locks funds on the destination chain. Only then does the user finalize their side by adding the hashlock that matches what the Solver used. This ordering ensures users can verify the Solver has locked before they commit fully.

The two-phase design also removes the secret management burden from users. In classic HTLCs, the user generates the secret and must store it safely until the swap completes. In TRAIN, the Solver generates the secret and reveals it when redeeming on the source chain. The user simply monitors for this reveal and uses it to claim on the destination. No secret storage required on the user side.

Solvers

Solvers are professional liquidity providers who compete to fulfill user swap requests. When a user wants to swap assets, they submit an intent to the Auction Manager. Solvers bid in a Dutch auction, offering exchange rates. The winning Solver then executes the swap by locking funds on the destination chain.

The protocol uses a reward-slash mechanism to keep Solvers honest. When locking funds, Solvers must also lock a reward amount. If they complete the swap before the reward timelock expires, they keep the reward. If they fail to act in time, whoever completes the redemption (the user or a third party) claims the reward. This creates a strong incentive for Solvers to follow through and compensates users if something goes wrong.

Because Solvers handle the destination chain transaction, users do not need gas on that chain. The user only transacts on the source chain. The Solver locks and the user redeems on the destination, but redemption can be done by anyone with the secret. In practice, Solvers often handle this too, or the protocol design allows gasless claims through signature-based flows where the Solver submits on behalf of the user.

TRAIN Atomic Swap Flow

Consider Alice swapping 1 ETH on Ethereum for USDC on Arbitrum.

Intent Submission: Alice submits a swap intent to the Auction Manager specifying source chain, destination chain, and amounts.

Auction: Solvers compete in a Dutch auction. Solver Bob wins by offering the best rate.

User Commit: Alice calls

commit()on Ethereum, locking 1 ETH in the PreHTLC contract. No hashlock yet.Solver Lock: Bob sees Alice's commitment, generates secret

Sand computesH = hash(S). He callslock()on Arbitrum, locking USDC with hashlockHand a reward amount.User AddLock: Alice sees Bob's lock on Arbitrum, extracts hashlock

H, and callsaddLock()on Ethereum to finalize her commitment with the sameH.Solver Redeem (Source): Bob calls

redeem()on Ethereum with secretS, claiming Alice's ETH. The secret is now public on-chain.Solver Redeem (Destination): Bob calls

redeem()on Arbitrum using the same secretS, releasing the USDC to Alice.

Alice only signed two transactions on Ethereum. Bob handled both Arbitrum transactions. If Bob never locked in step 4, Alice calls refund() after timeout. If Bob locked but Alice never added the hashlock, Bob refunds on Arbitrum after his timelock expires.

Multi-Hop Swaps

Not every chain pair has a Solver with direct liquidity. TRAIN handles this through multi-hop routing. If a user wants to go from Chain A to Chain C but no single Solver covers both, two Solvers can chain together: one for A→B and another for B→C. The same hashlock propagates through all hops, maintaining atomicity. The user still only submits two transactions on the source chain regardless of how many hops are involved.

Custom Flows

Some chains have unique requirements that the standard flow cannot handle. TRAIN supports custom flows for these cases. Aztec is one example. Aztec is a privacy-focused network where user identity must remain hidden. The standard TRAIN flow would expose the user through on-chain transactions. The Aztec custom flow uses public protocol logs that reveal swap state and identifiers without revealing user identity. Users encode an ownership proof into their commitment, which binds the destination lock to them without exposing who they are. Solvers coordinate using these public signals while user privacy is preserved. The TRAIN documentation covers this in detail.

Problems Addressed

TRAIN directly addresses the classic HTLC limitations discussed earlier. Users do not manage secrets since Solvers generate them. Users do not need gas on the destination since Solvers handle that side. Users do not need to stay online for the entire swap window since the two-phase commitment gives them flexibility on timing. The auction mechanism and reward-slash system handle the griefing and option problems by making Solvers compete on price and penalizing them for abandoning swaps. The protocol deploys immutable, non-upgradable contracts across supported chains including EVM networks, Starknet, Solana, TON, and Aptos.

Atomic Swaps vs Bridges

Atomic swaps exchange native assets directly using HTLCs with no wrapped tokens or custodians. Security is enforced at the protocol level. Bridges use lock-and-mint: lock tokens on one chain, mint wrapped versions on another. Bridges work across incompatible chains but require trusting that wrapped tokens are backed by locked originals. Bridge hacks have caused billions in losses due to this trust assumption.

Choose atomic swaps when trustless execution matters and chains are compatible. Choose bridges when you need access to incompatible chains or instant liquidity pools. Atomic swaps are stronger on security; bridges are stronger on flexibility.